The Mediterranean breeze welcomes me in a warm hug as I step off the plane and onto the tarmac. After two rainy days in Edinburgh we had made it to Marseille, gritty and historical port town in the south of France. Most travellers do not linger here, opting instead for the more glamorous St. Tropez, Nice or Cannes further along the coast, but those who do are absorbed into a truly international rhythm. Known more for it’s multicultural markets and food scene than its beaches, I was salivating before I got off the plane.

Almost immediately I am reminded at how ashamed my grade school French teacher would be of me. I open my mouth to figure out which bus will take us to the central train station and vomit out a jumble of nouns and invented word tenses instead. A friendly English speaking woman takes pity and informs us that there is a country-wide transportation strike, an inconvenience that will throw a wrench in more than one of our travel plans in the days to come. She points us in the direction of the paid airport shuttle and leaves us with a rather ominous warning, “In Marseille, keep a close eye on that,” gesturing to my purse. “Welcome to the South of France.”

***

Marseille’s St Charles train station provides one of the more dramatic introductions to a city that I have ever seen. Perched high a top a hill, the first views as you exit are rows of terracotta –coloured rooftops stretching towards the Mediterranean Sea. by A pair of stone lions guard the staircases leading down to the concrete, graffiti-filled jungle. Garbage litters the sidewalks where Muslim men wearing taqiyahs stroll alongside women dressed in bold, African prints. Moroccan tearooms and Tunisian pastry shops line the narrow streets next to pizzerias with wood fire ovens cooking pies that would make Naples proud. The rest of the world began molding this port town into something uniquely Marseillaise long ago, a phonology all it’s own. Officially named the European Cultural Capital in only 2013, Marseille must have wondered why it took everyone else so long to catch on.

It’s Sunday and France is playing their first match in the World Cup against Honduras. We assimilate into the crowd that has gathered in front of a pub broadcasting the game through the windows on tiny TV’s and jump on the bandwagon. Chants of “Allez les Blues! Allez!” echo across the otherwise tranquil harbor.

It is not until after France has easily handled their first opponent and the crowd begins to disperse that we meet Bernard. Perched atop one of the bar stools in a black cut off T-shirt and cowboy hat dangling from a string around his neck, he appears to have had one glass too many of the rose spritzer sloshing around in his cup. He looks to be about 65, exposure to the elements deepening the lines on his leathery skin.

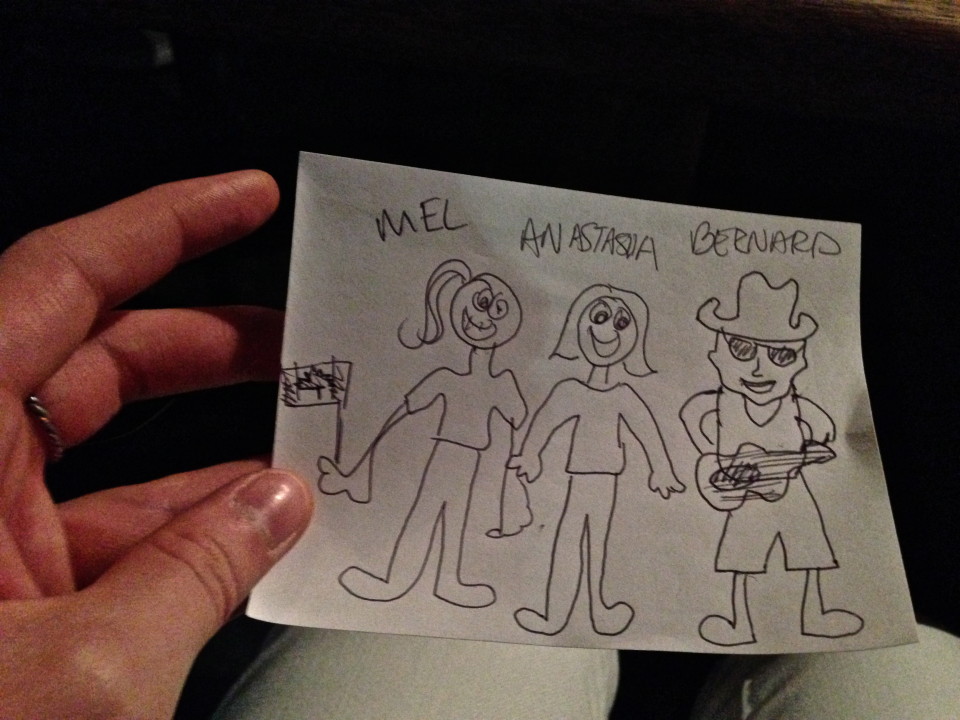

Eye contact is made and we are now the center of Bernard’s world (and by association the center of attention in the pub). My limited French vocabulary becomes too tedious for Bernard, so off he goes to the bar for a pen and pad of paper. Through scribbled down words and pictures I learn that he made a living fishing and that he has both sailed around the Horn of Africa and seen the Northern Lights in his day. He is a fan of Tony Parker and most certainly not an artist.

A song peaks Bernard’s interest and he jumps out of his seat, transforming into his alter ego as he carefully pulls on his dark sunglasses and cowboy hat. He serenades us with his best air guitar rendition of Eric Clapton’s Cocaine, all 4 minutes and 20 seconds of it. The sight is so ridiculous that part of me is embarrassed, growing hotter with each new pair of eyes that Bernard’s performance is attracting. The rest of me can acknowledge that these are really my own insecurities, and even admire his indifference to the stares around the bar. I decide to concede, take a sip of my pint and holler, “play it Bernard!” Bernard is emboldened by our support and keeps us laughing until our glasses are empty and it is time to say goodnight.

On my last night in Marseille I decide to bring my carefully curated finds from the nearby Noailles market to the vieux port, where I envisioned eating my dinner in peace while watching life float by.

No sooner had I swung my legs over the pier and begun to unpack my dinner than did two middle-aged men decide to plop down beside me. Irked by their proximity and not in the mood to entertain, I pretend to be intently consumed by my seafood paella.

Bernard (yes another Bernard, I swear), however, is persistent. His friend Michèle is squat and tanned with a glow about him that makes it seem as if he had been slow roasting inside an oven all day. While Bernard insists on making small talk, Michèle leans back idly with one arm draped over his bent knee gazing off across the harbor as it turns an expensive shade of gold.

Just as I feared, we exchange pleasantries in broken French and struggle to discuss the city and the sunset. As patient as he is persistent, Bernard smiles and encourages, “in Toronto, I practice English, but in Marseille you must practice French.” Unable to argue with this logic, I lower my guard (and reluctantly my dinner) and give my new teacher my full attention. I decide not to mention that I studied French for the better part of my middle school years, thinking it best to set the bar low. I manage to explain how it is this girl from Toronto has found herself sitting alone in the harbour eating paella (“You come all the way to France to eat Spanish food!” Bernard quips) in between visiting European schools on ‘official’ work business.

At the mention of my visiting Noeilles market and purchasing some savon du Marseille – a type of soap that is made in the city and famous for it’s high content of olive oil – Michèle, indifferent up until this point, suddenly comes to life. I passed him a Lavender-scented bar from my bag and he breaths it in deeply, the smell momentarily transporting him to another time and place. He then begins to animatedly mime the soap’s multiple purposes, from washing his body to keeping his head shaved bald, starring intently at me as if to ensure that I don’t miss a single silent word.

Golden hour has almost past and I ask Bernard if the view here ever gets old. He assures me that it does not. “Le belle vie, oui!?” I remark unconvincingly, unsure of my syntax. Bernard smiles, pleased at his quick study. “Oui, la vie est belle,” he corrects. I say farewell, marvelling at language’s little subtleties as I leave the cobblestone of the old port behind.

Throughout my travels in Marseille I encountered characters eager to show me the best side of their city, and each time my regret was that I could not communicate more fully with them. As an Anglophone abroad I am constantly reminded of my ignorance, thankful that the rest of the world decided to put a little more effort into their second language classes than I. Language is the key to unlocking our understanding of a place and the people in it, and nowhere does its importance become more apparent then when you find yourself surrounded by unfamiliar tongues. Not surprisingly, this is also when I am most grateful for how much can be conveyed through nonverbal gestures — from our tone, pitch, posture and body language. I find myself thankful that our shared experiences and humanity enable us to communicate across borders, when we care to listen.

Leaving Marseille I made a pledge to continue to practice my French. But I will also remember that, despite all that may be lost in translation, we can always find other ways to connect – through a smile, some charades, or even an Eric Clapton song.

No Comments